TCP Socket Programming

The Transport Layer in the TCP/IP model is responsible for ensuring that data is correctly transmitted between source and destination. It includes two key protocols: TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) and UDP (User Datagram Protocol). TCP enables reliable, connection-oriented, and error-controlled data transfer between endpoints, ensuring data integrity and proper delivery. In contrast, UDP offers connectionless communication, prioritizing speed over reliability by transmitting data without error checking or correction mechanisms. In this page we will see the working of TCP protocol in more detail and the socket programming system calls that enables this connection oriented communication..

TCP Protocol

Let us look into the TCP Protocol in detail. TCP ensures that all the data transmitted by the sender is received by the recipient in the correct order. If packets are lost, TCP will re-transmit them until they are correctly received. Thus the TCP Protocol ensures a reliable transmission of data. Before any data is sent, TCP requires a connection to be established between the client and server. This connection setup involves a three-way handshake. The data transmission takes place only after the connection gets established. Finally the connection has to be terminated gracefully.

The Phases of TCP operations

The working of TCP protocol can be broadly divided into three different phases. These steps fit into three main stages:

Connection Establishment: TCP uses a three-way handshake (SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK) to establish a reliable connection between a client and a server, ensuring that both are ready for communication. Three way handshake involves the following steps:

Server creating a listening socket - Initially the server that is willing to accept client connections must have created a listening socket using the

socket()system call and bound the listening socket to the specific port using thebind()system call and executedlisten()system call to inform the kernel that it is waiting for clients requesting connection to the port. Upon execution of thelisten()system call, the kernel sets up two queues on the server side - a request queue (also called SYN queue) and an accept queue. The maximum length of the accept queue can be specified as an argument to thelisten()system call. (However, the kernel may restrict the lengths of the queues.)Client initiates the connection - When the client calls the

connect()system call using a TCP socket, specifying the IP address and port number of the server, a SYN packet is send to the server signaling the client’s intent to establish a connection. If the server has not executed alisten()on the socket when the SYN packet arrives, the server kernel will immediately reject the SYN with a RST (Reset) packet and theconnect()will fail with the error connection refused.Server Acknowledges - If the server has already called

listen(), the server side OS kernel will place the SYN packet in the request queue as a half-open connection. The server side kernel will then respond with a SYN-ACK packet to the client machine indicating that server is ready to accept the connections. The connection remains in the request queue until the client sends the final ACK packet. The client program will remain blocked inside theconnect()system call till SYN-ACK/RST is obtained.Client Confirms - Upon receipt of the SYN-ACK packet, the client side kernel acknowledges the server side kernel by sending an ACK packet. This completes the 3-way-handshake process. The

connect()system call will return success to the client program at this point.Connection establishment - On receiving the ACK from client, the server side kernel now moves this fully established connection from the request queue to the accept queue (also called the completed connection queue). Once this step is complete, the connection is fully established. If the server fails to receive ACK from the client at time out, then the SYN-ACK packet is re-transmitted and the client must sent ACK again. (These attempts could be repeated a few times (typically 5 times by most Linux kernels) to take care of packet losses, and the connection is dropped from the request queue if three-way-handshake fails to get completed.) The accept queue holds connections that are fully established but are waiting for the server to call the

accept()system call. Theaccept()system call will block till the accept queue is non-empty.Each entry in the accept queue represents a client that has successfully established the connection. After the three-way handshake in TCP, when the server calls

accept(), the first fully established connection in the accept queue is retrieved. At this point, the kernel creates a new dedicated socket called the connection socket on the server side for communication with that specific client. This new socket (bounded to same port as the listening socket) is distinct from the original listening socket and is used exclusively for data exchange with that particular client. The original listening socket continues to listen for new incoming connections, and is not used for data transfer. Each TCP connection is thus uniquely determined by the four tuple - (server IP, server port, client IP and client port).

Data Transmission: Data transmission in TCP occurs through the

send()andrecv()system calls. Since the connection is already established, these functions do not require specifying the target address, as the kernel on the respective machine (client/server) identifies the socket with the corresponding connection internally.Here are some internal details on how

send()andrecv()system call works.When the

send()system call is used, the data from the user’s buffer is first copied into the kernel send buffer of the corresponding socket. Thesend()call returns success as soon as the data is copied, but this does not guarantee that the data has reached the receiver. If there is insufficient space in the kernel buffer for the requested data,send()will block until space becomes available (unless the socket is in non-blocking mode, in which casesend()returns immediately with an error). Each socket maintains a send queue and a receive queue in the kernel to manage outgoing and incoming packets. During transmission, the data is broken into smaller segments based on the Maximum Segment Size (MSS), which is determined during connection establishment when both sides exchange their MSS values in SYN and SYN-ACK packets. The final MSS is set to the lower of the two values (acceptable to the client and the server kernels) to ensure compatibility. These segmented packets, wrapped with TCP headers containing sequence numbers and check sums, are placed in the send queue of the socket. The kernel's TCP logic then transmits these packets over the network. Upon successful reception, the receiver sends an ACK packet acknowledging the data. Once the sender receives this ACK, the corresponding data is removed from the send queue and memory is freed. If no ACK is received within the Retransmission Timeout (RTO), the kernel re-transmits the unacknowledged packets.On the receiving side the incoming packets need not be in the same order as send by the other side. The packets may arrive out of order due to network congestion or other related issues. Thus it is essential to reorder the data correctly at the receiving side. There is a receive queue and an out-of-order queue maintained by the kernel for each connection socket. When packets arrive out of order, they are placed in the out-of-order queue until the missing packets arrive, and then they are reordered and moved into the receive queue. When the application calls

recv(), it requests a specific amount of data from the receive queue. If the queue is empty,recv()blocks (unless the socket is in non-blocking mode) until data arrives. Otherwise, the kernel copies the requested data from the receive queue to the user-space buffer, returning success once the copy is complete. If the available data is less than requested,recv()returns only what is available. If the available data in kernel receive queue exceeds what is requested, the remaining data will continue to be stored in the kernel receive queue till the anotherrecv()operation extracts it. These mechanisms, along with sequence numbers, ACKs, retransmissions, and proper queue management, ensure TCP's reliability and in-order data transfer.Note that in UDP, which is a connection-less protocol, there is no formal connection setup using

listen(),connect(), oraccept(). Hence each packet must carry explicit addressing information. The sender must specify the target address in eachsendto()call, and the receiver retrieves the sender's address usingrecvfrom()to know where to respond. (More details on UDP is provided in the UDP documentation.)Connection Termination: The connection is closed gracefully using a four-way handshake (FIN, ACK, FIN, ACK), allowing both parties to end communication without data loss. The termination process typically begins when one side (typically the client) initiates the termination by calling the

close()system call. As a result the client side kernel send a FIN packet to the server. Upon receiving the FIN, the server side kernel acknowledges it by sending an ACK packet back to the client. At this point, the connection becomes half-closed, meaning the client can no longer send data, but the server can still transmit data to the client and the client can receive the data from server. This half-closed state ensures that all the pending data reaches the destination before the connection fully terminates. Once the server completes its data transmission, it must invokeclose()to intimate the server kernel of its willingness to close the connection. At this point, the server side kernel sends its own FIN packet to the client. The client, upon receiving this FIN, responds with a final ACK packet,and releases the resources associated with the client socket. After receiving the final ACK, the resources associated with the server socket gets released.

Socket Programming

Sockets are software structures that serve as endpoints for communication. Sockets enable bidirectional data transfer, meaning they allow both sending and receiving data across a network. Sockets are commonly used to enable inter-process communication. When two processes, whether on the same machine or different machines, need to communicate over a network, each process must create its own socket, and the communication occurs through these two sockets. In Unix/Linux systems, sockets are treated as file descriptors. Therefore like regular files, sockets can also use standard file operations like read(), write(), close() and so on. In Unix/Linux systems, the socket programming interface is defined in the sys/socket.h header. It offers a set of functions that applications can use to perform tasks like establishing connections, sending and receiving data, and closing connections. Each network socket is associated with an IP address and a port number, which together identify both the host and a specific application or service. A socket address is the combination of the IP address and port number. Sockets are widely used in client-server networks to enable communication between the client and server.

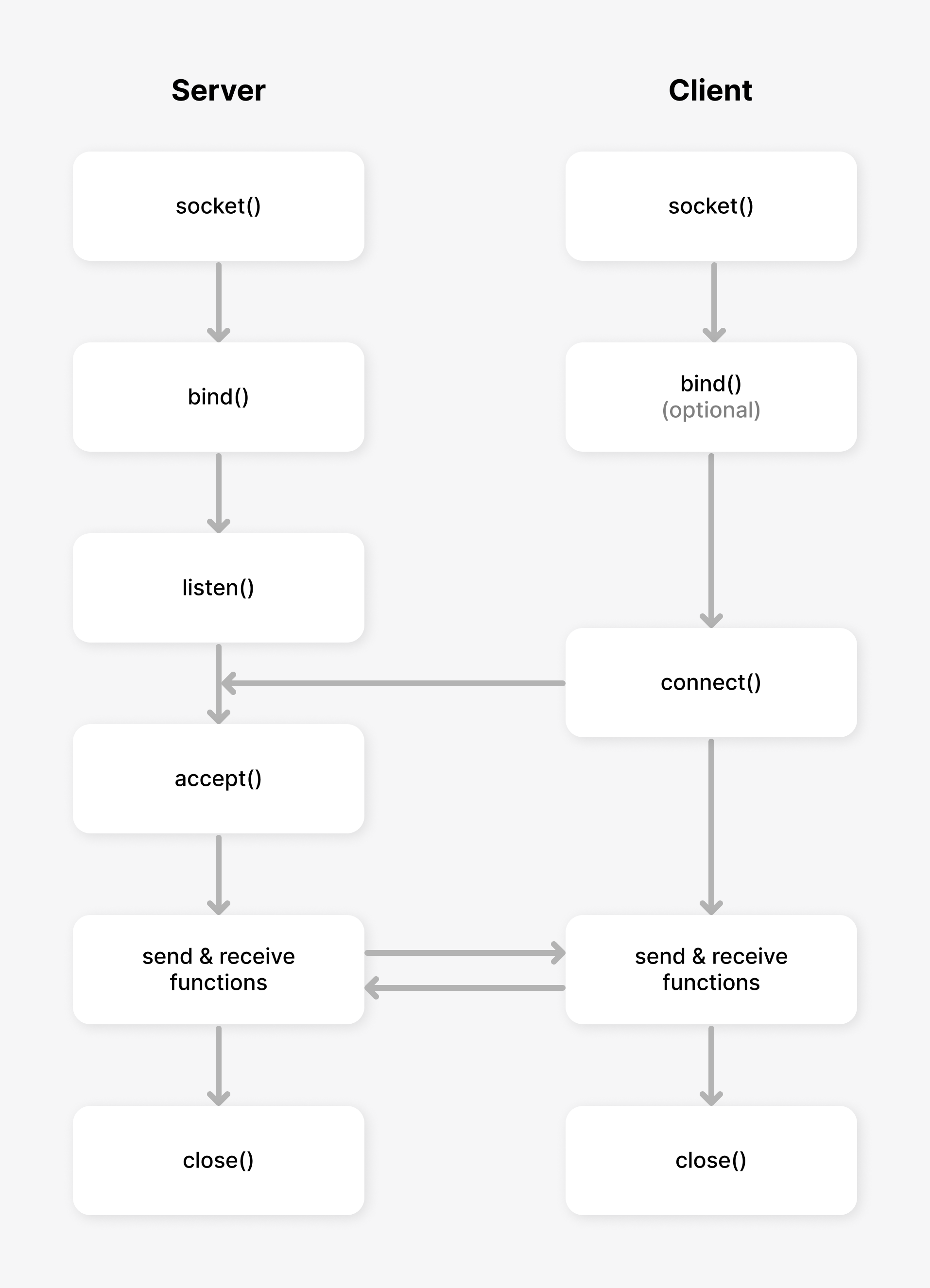

Socket programming follows a typical flow of events. The figure below illustrates the sequence of events (and function calls) for a connection-oriented socket session using TCP. We will then look at the various system calls used in socket programming in more detail.

Socket creation: When an application process wants to communicate over a network, the first step is to create a socket using the

socket()system call. A socket serves as the communication endpoint that enables data transmission between the application and the network.The

socket()system call is declared in the<sys/socket.h>header, which provides the definitions needed for socket programming in C.

#include <sys/socket.h>

int socket( int domain, int type, int protocol );The arguments of socket() system call are as follows:

int domain- Thedomainargument is an integer value that specifies the communication domain. It defines the addressing scheme and the network protocol that will be used for communication. Common values for this argument include:AF_INET: for IPv4 communication (32-bit IP addresses)AF_INET6: for IPv6 communication (128 bit IP addresses)int type- The type argument is also an integer value that specifies the socket type, which defines the communication semantics or how the data will flow between the client and server. Common values for this argument include:SOCK_STREAM- Provides sequenced, reliable, two-way, connection-based byte streams. This type is typically used with TCP (Transmission Control Protocol), which ensures reliable, ordered data delivery.SOCK_DGRAM- Supports connectionless, unreliable messages of a fixed maximum length. This type is used with UDP (User Datagram Protocol).The following options, although not utilized in this project, are also available:

SOCK_RAW- Provides access to raw network protocols, allowing low-level network communication. This option is available only for processes with root privilege.SOCK_SEQPACKET- Offers a reliable, sequenced, two-way connection-based communication path for fixed-length datagrams. It preserves message boundaries ensuring the whole message is read at once unlike TCP, where message is sent as a byte stream.NOTE -

SOCK_SEQPACKETis not used with TCP or UDP protocols. It is commonly used in UNIX domain sockets (AF_UNIX) in inter-process communication to exchange fixed-length messages reliably. It is used mainly with the SCTP protocol.int protocol- Theprotocolargument is of integer type that specifies the specific protocol to be used with the socket. When0is passed as the protocol argument, the system automatically selects the default protocol for the given combination of domain and type. For example, withAF_INET(IPv4) andSOCK_STREAM, the default protocol is typically TCP, since it is the default protocol for stream sockets in the IPv4 domain. To explicitly specify a protocol, protocol numbers likeIPPROTO_TCP,IPPROTO_UDP, orIPPROTO_RAWcan be used.

Return Value : On success, socket() returns a file descriptor for the newly created socket. On failure, it returns -1, and the global variable errno is set to indicate the specific error. (eg: If an invalid domain, type, or protocol is specified, errno might be set to values like EINVAL (invalid argument) or EPROTONOSUPPORT (protocol not supported). If the system is out of resources or has reached a limit on the number of open file descriptors, errno could be set to EMFILE or ENFILE )

Binding : When a socket is created using the

socket()system call, it doesn’t have an associated address. Thebind()system call is used to assign an IP address and port number to the socket . In server applications,bind()is used to bind the socket to a specific IP address and port number, allowing the server to listen for incoming connections on that address and port. For client sockets, binding is not required, as the operating system automatically assigns a local IP address and an available port number (from ephemeral port range) when establishing a connection. In general the operating system allows only one socket to be bound to a specific port on a host at any given time.The

bind()system call is included in the<sys/socket.h>header.

#include <sys/socket.h>

int bind ( int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen );The arguments of bind() system call are as follows:

int sockfd- Thesockfdargument specifies the file descriptor of the socket to be bound. This file descriptor is typically obtained by calling thesocket()system call earlier.const struct sockaddr *addr- A pointer to a variable of typestruct sockaddrthat contains the address to be bound to the socket. The caller is responsible for declaring and initializing this variable. More details onstruct sockaddris provided below:struct sockaddrThesockaddrstructure is used to define a socket address. It is a general structure used to represent a socket address in a protocol independent way (it is used with both IPv4 and IPv6). It is typically used in functions likebind(),connect()andaccept(), when the specific address structure is not known at the compile time. The<sys/socket.h>header shall define the sockaddr structure that includes the following members:cstruct sockaddr{ sa_family_t sa_family //Address family. char sa_data[] //Socket address of the data stream(variable-length data). };sa_family_tis defined as an unsigned integer type in<sys/socket.h>header. The sa_family argument is used to denote the socket’s address family.(eg AF_INET is used with IPv4 , AF_INET6 is used with IPv6, AF_UNIX for unix domain sockets )sa_datais a character array that holds the actual address, which varies depending on the protocol. In case of IPv4, sa_data stores an IPv4 address, which consists of the IP address (4 bytes) and the port number (2 bytes). In case of IPv6, sa_data that stores an IPv6 address, which consists of the IP address (16 bytes) and the port number (2 bytes). As thestruct sockaddris a generic address structure, it cannot directly hold an IPv4 or IPv6 in a fully usable form. Thus we don’t declare and initializestruct sockaddrdirectly in the code. Instead a specialized version ofstruct sockaddrnamedstruct sockaddr_inis used for IPv4 addresses andstruct sockaddr_in6is used for IPv6 addresses. These specific address structures are then typecast intostruct sockaddr. Thestruct sockaddr_inis a specialized address structure used typically with IPv4 addresses. This structure is defined in the<netinet/in.h>header. The fields are as follows:

cstruct sockaddr_in { sa_family_t sin_family;/*AF_INET*/ in_port_t sin_port;/* Port number */ struct in_addr sin_addr;/* IPv4 address */ }; struct in_addr { in_addr_t s_addr; };sa_family_t: This is a data type used to represent address family in socket programming. It is defined as an unsigned integer type in<sys/socket.h>header. Insockaddr_inthe fieldsin_familyis of this type. This field specifically holdsAF_INETwhich denotesIPv4address family.in_port_t: This is a data type used to represent port number in socket programming. It is defined as an unsigned 16 bit integer in<netinet/in.h>header. (Since it is an unsigned 16-bit integer, it can hold values in the range from 0 to 65535, which corresponds to the valid port range). It holds port numbers in network byte order (big-endian format). Functions likehtons()(host-to-network short) are used to convert the port number from host byte order to network byte order. (egin_port_t port = htons(8080);)struct in_addr: This is a structure that represents IPv4 addresses in network byte order. It has a single field of typein_addr_t, which actually stores the 4 byte IPv4 addresses.in_addr_t: This is a data type used to store IPV4 address in network byte order. This is defined as an unsigned 32 bit integer in the<netinet/in.h>header. Usually in the code we use IP addresses in standard dotted decimal string representation (e.g.,"192.168.1.1"). Thus to convert this intoin_addr_t, a function namedinet_addr()can be used. It automatically stores the value in network byte order. NOTE: network byte order refers to the standard way in which data is transmitted over a network. It follows the big-endian format. Host byte order refers to byte order used by a particular machine to store multi byte data. It can be either big endian or little endian depending on the architecture of the machine. In big-endian format, the most significant byte (MSB) is stored first, at the smallest memory address. In little-endian format, the least significant byte (LSB) is stored first, at the smallest memory address. In case of IPv6,struct sockaddr_in6is used instead ofstruct sockaddr_in. The structure ofstruct sockaddr_in6is as follows:

cstruct sockaddr_in6 { sa_family_t sin6_family;/*AF_INET6*/ in_port_t sin6_port;/* Port number */ uint32_t sin6_flowinfo;/* IPv6 flow info */ struct in6_addr sin6_addr;/* IPv6 address */ uint32_t sin6_scope_id;/* Set of interfaces for a scope */ }; struct in6_addr { uint8_t s6_addr[16]; };This is similar to

struct sockaddr_inexcept that there are additional fields for flow information and scope of interfaces. Here the family field should be set to IPv6 and IP address will be of 128 bits. Port number is 16 bits itself as in IPv4. In eXpserver we will be working with IPv4 addresses only thus we mainly deals withstruct sockaddr_inin the project.

socklen_t addrlen- it specifies the length of thesockaddrstructure pointed to by theaddrargument. This length is necessary because the operating system needs to know how much memory to read for the address, as different address families can use structures of different sizes. (socklen_tis of unsigned integer type)Return Value : On success,

bind()returns0. On failure, it returns-1, and the global variableerrnois set to indicate the specific error. Common errors forbind()includeEADDRINUSE, which occurs when the address is already in use by another socket;EACCES, which indicates the process doesn't have permission to bind to the address;EINVAL, when the address is invalid; andENOTSOCK, which means the provided file descriptor is not a valid socket.

Listening (Server only) : Servers transition to a listening state using the

listen()system call, signaling their readiness to accept incoming connections from clients. Thelisten()function marks the socket, as a passive socket. A passive socket is one that is prepared to accept incoming connection requests, but does not actively initiate connections itself.The

listen()system call is included in the<sys/socket.h>header.

#include <sys/socket.h>

int listen ( int sockfd, int backlog );The arguments of listen() system call are as follows:

int sockfd- Thesockfdis the file descriptor (of the server) that refers to a socket of typeSOCK_STREAMorSOCK_SEQPACKET, which is used to listen for incoming connections. This is the file descriptor for the socket that was created usingsocket()and typically bound to an address usingbind().int backlog- Thebacklogargument defines the maximum length to which the queue of pending connections for the socket (sockfd) can grow. if backlog less than 0, the function sets the length of the listen queue to 0 (which means that any connection request TCP packet received after receipt of one will be rejected till anaccept()is executed on the current request). If the listen queue is not of length 0, backlog determines the number of requests that can be queued. Iflisten()is passed with a backlog value that exceeds the maximum queue length permitted by the OS, the length will be set to the maximum supported value.

Return Value : If the listen() call succeeds, it returns 0, signaling that the server socket is now ready to listen for incoming connections. If an error occurs, the function returns -1 and sets the errno global variable to indicate the type of error. Common error for listen() include, EBADF - when the socket descriptor is invalid, EOPNOTSUPP - when the socket doesn't support listen() like in UDP.

Connection Establishment (Client) : Clients establish a connection to the server using the

connect()system call, where they specify the server's address and port. This call creates a connection with the server, enabling data exchange. A connected client socket attempting to connect to the same server again will result in an error, stating that the transport endpoint is already connected.The

connect()system call is included in the<sys/socket.h>header.

#include <sys/socket.h>

int connect( int sockfd, const struct sockaddr * addr, socklen_t addrlen );The arguments of connect() system call are as follows:

int sockfd- Specifies the file descriptor associated with the socket (of the client), which is created using thesocket()system call. This file descriptor is used to refer to the socket on which theconnect()system call is being invoked.const struct sockaddr * addr- It is a pointer to asockaddrstructure that contains the server address to which the client wants to connect. The caller (in this case, the client) must declare and populate the fields of this structure. The format and length of the address depend on the address family of the socket.socklen_t addrlen- Specifies the length of thesockaddrstructure pointed to by theaddrargument. This length is necessary because the operating system needs to know how much memory to read for the address. Different address families (such asAF_INETfor IPv4 orAF_INET6for IPv6) use structures of different sizes, so the length must be provided.

Return Value : If the connection succeeds, zero is returned. On error, -1 is returned, and errno is set to indicate the error. The common errors include, ECONNREFUSED - occurs when there is no host listening on the port, ETIMEDOUT - when the connection attempt is timed out, EHOSTUNREACH - when the host is unreachable.

Accepting Connections (Server): When a server receives a connection request from a client, it accepts the connection using the

accept()system call, which creates a new socket specifically for communication with the client. This new socket will have the same type and family as the listening socket. Theaccept()call is used with connection-based socket types (such asSOCK_STREAMorSOCK_SEQPACKET) to accept an incoming connection on a listening socket. It extracts the first connection request from the queue of pending connections for the listening socket and creates a new connected socket that shares the same socket type, protocol, and address family as the original listening socket, and returns a new file descriptor for this newly created socket. This new socket is ready for communication with the client, while the original listening socket remains unaffected and continues to listen for new incoming connections.The

accept()system call is included in the<sys/socket.h>header.

#include <sys/socket.h>

int accept ( int sockfd, struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t *addrlen );The arguments of accept() system call are as follows:

int sockfd- Refers to the listening socket that is in a passive state, waiting for incoming connection requests from clients. The socket is created withsocket(), bound to a specific local address and port withbind(), and put into the listening state withlisten().struct sockaddr *addr- It is a pointer to asockaddrstructure, which is used to receive the address of the connecting entity (the client). The caller is responsible for initializing and allocating space for this structure. The OS kernel then populates the fields of thesockaddrstructure with the client's connection details (such as the client's IP address and port). The client does not set this structure in theconnect()system call; instead, it is filled by the kernel during theaccept()call after the connection is established.socklen_t *addrlen- A pointer to asocklen_tvariable, which specifies the length of thesockaddrstructure on input, and on output, it will contain the length of the address that was stored in thesockaddrstructure.

Return Value : On success, the accept() system call returns a non-negative integer that represents a file descriptor for the newly accepted socket. This new socket is used for communication with the client. On error, -1 is returned, errno is set to indicate the specific error that occurred, and the addrlen parameter is left unchanged. The common error include, EBADF - when the socket descriptor is invalid, ECONNABORTED - the connection was aborted before accept() was called.

send()- Once the connection is established, both the client and server can send and receive data using thesend()andrecv()system calls, respectively. Data sent by one party is received by the other, allowing for bidirectional communication. Thesend()system call is used to transmit data from a socket to a connected peer. It is applicable only when the socket is in a connected state, where the recipient’s address is already known. This applies to TCP sockets, where a connection is first established usingconnect()(on the client side) oraccept()(on the server side). When a process callssend(), the data is first copied into the kernel send buffer of the socket. If there is sufficient space in the buffer, the system call completes successfully, and returns. Thus the success ofsend()doesn’t mean data has reached the destination. It implies data has been copied from user buffer to kernel buffer. If the message to be sent is too large to fit into the socket's kernel send buffer, thensend()call will typically block, waiting for space to become available in the buffer. However, if the socket is set to non-blocking I/O mode,send()will return immediately, and an error likeEAGAINorEWOULDBLOCKwill be returned instead of blocking. (By default the sockets created will be in blocking mode.)The

send()system call is included in the<sys/socket.h>header.

#include <sys/socket.h>

ssize_t send( int sockfd, const void *buf, size_t len, int flags );The arguments of send() system call are as follows:

int sockfd- This is the socket that will be used to send the data. It is a valid file descriptor returned by thesocket()call (and potentially connected viaconnect()oraccept()for communication).const void *buf- This is a pointer to the memory buffer containing the data to send. The data to be transmitted is placed in this buffer. It is declared and populated by the caller.size_t len- This specifies the number of bytes to send from the buffer. It tells thesend()function how much data to transmit from the memory pointed to bybuf.int flags- This argument specifies various options that can modify the behavior of thesend()call. Some common flag values include.MSG_CONFIRM: Ensures that the destination address is reachable. This is typically used in specific protocols like UDP.MSG_DONTWAIT: Sends data without blocking, similar to non-blocking mode. Here if space is not available in the kernel buffer send() will immediately fail.

Return Value : On success, the send() system call returns the number of bytes actually copied from user buffer to the kernel buffer. This number may be less than the number of bytes requested to be sent, especially if the message could not be entirely buffered in one call (for example, due to network congestion or buffer limitations). On error, send() returns -1, and the global variable errno is set to indicate the specific error that occurred. The common errors include EAGAIN (copy to kernel buffer failed) or EWOULDBLOCK (returning without performing the operation to avoid blocking) when the socket is in non-blocking mode, and there is no space in the kernel send buffer to accommodate the data. ENOTCONN is returned when the socket is not connected to any peer. EHOSTUNREACH when the destination host is unreachable, possibly due to network issues.

recv()- Therecv()system call is used to receive data from a connected peer through a socket. It is applicable only when the socket is in a connected state, where the sender’s address is already known. This applies to TCP sockets, where a connection is first established usingconnect()(on the client side) oraccept()(on the server side). When a process callsrecv(), the data is copied from the socket’s kernel receive buffer into the user-provided buffer. The success ofrecv()indicates that the data is copied from kernel buffer to the user buffer. But it does not mean that all expected data has been received. If the received data is larger than the buffer provided by the application, only the portion that fits will be copied, and the remaining data will stay in the kernel receive buffer for subsequentrecv()calls. Whenrecv()is called if there is already data available in the kernel buffer,recv()immediately returns with the received data. However, if there is no data available, the behavior depends on whether the socket is blocking or non-blocking. In case of blocking sockets if there is no data available in the kernel buffer whenrecv()is called, then it would block until some data is available in the kernel buffer. In non-blocking mode,recv()will return immediately with an error (EAGAINorEWOULDBLOCK) if no data is available.The

recv()system call is included in the<sys/socket.h>header.

#include <sys/socket.h>

ssize_t recv ( int socket, const void *buf, size_t length, int flags );The arguments of recv() system call are as follows:

int socket- the file descriptor of the socket from which the data will be received. It represents a socket that has already been established as part of a connection, meaning the socket is either connected to a remote server (for client-side sockets usingconnect()) or is part of an accepted connection (for server-side sockets usingaccept()).const void *buf- This is a pointer to a memory buffer that the caller provides, where the received data will be stored. The buffer is declared and allocated by the caller before callingrecv(). The data received from the socket is placed into this buffer by therecv()function.size_t length- This specifies the maximum number of bytes that can be received and stored in the buffer. Therecv()function will attempt to receive this amount of data (or less, depending on what is available) and return the actual number of bytes received.int flags- Specifies options that can modify the behavior of therecv()call. Some common flags includeMSG_DONTWAIT- it makesrecv()non-blocking, similar to setting the socket to non-blocking mode. If no data is available in the receive kernel buffer,recv()returns immediately with an error (EAGAINorEWOULDBLOCK),MSG_WAITALL- instructsrecv()to wait until the full requested amount of data is received etc.

Return Value : On success, the recv() system call returns the number of bytes actually copied from the kernel receive buffer to the user buffer. This number may be less than or equal to the requested size, depending on the amount of available data. If no data is available and the socket is in blocking mode, recv() will block until some data arrives. If the client terminates the connection with the close() system call, then a FIN packet is sent from the client to the server and the recv() returns 0.

If the socket is in non-blocking mode and no data is available, recv() returns -1 and sets errno to EAGAIN or EWOULDBLOCK. On error, recv() returns -1, and errno is set to indicate the specific error. The common errors include ECONNRESET - when the connection was forcibly closed by the peer (common in TCP when the other side sends a reset), ENOTCONN - when the socket is not connected to any peer. EFAULT – The user buffer provided for storing received data is invalid (inaccessible memory region).

- Connection Termination: When communication is complete, either party can initiate the termination of the connection using the

close()system call. This releases the allocated resources associated with the socket and terminates the communication channel.

close()Header :#include <unistd.h>int close(int fd);Description : closes a file descriptor, so that it no longer refers to any file and may be reused. Return Value : returns zero on success. On error, -1 is returned, and errno is set to indicate the error.

Blocking and Non Blocking sockets

Sockets can operate in two modes namely blocking or non-blocking. When a blocking socket performs an I/O operation, the program will pause and wait until the operation is completed. But in case of non-blocking sockets the program will immediately return with an error, even if the operation is not completed. For example, during send() the data from user buffer is copied to kernel buffer, But if the kernel buffer is full, then in case of blocking sockets the program will gets blocked (it means the program gets paused and will be in waiting state) until space is available in the kernel buffer. In case of non-blocking sockets if kernel buffer is full and send() cant be performed, then it will immediately return with an error instead of waiting until space becomes available.

Generally all the sockets created using socket() system call are in blocking mode. In Unix like systems, fcntl system call can be used to set a socket to non blocking mode. After socket() creation add the O_NONBLOCK flag using fcntl() to make the socket non blocking.

int sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

int flags = fcntl(sockfd, F_GETFL, 0);

if (flags == -1) {

perror("fcntl F_GETFL");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

if (fcntl(sockfd, F_SETFL, flags | O_NONBLOCK) == -1) {

perror("fcntl F_SETFL O_NONBLOCK");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}