Process and Threads

An executable program stored on a system’s hard disk typically contains several components, including the text (the executable code), statically defined data, a header, and other auxiliary information such as the symbol table and string table etc. When the operating system's loader (typically the exec system call in Unix/Linux systems) loads the program into memory for execution, a region of memory (logically divided into segments in architectures that support segmentation, such as x86 systems) is allocated to the program. Each of the program parts, such as the program text and static data, is loaded into separate segments of this allocated memory, called the text segment, data segment respectively.

This link provides more information about segmentation in x86 archiectures.

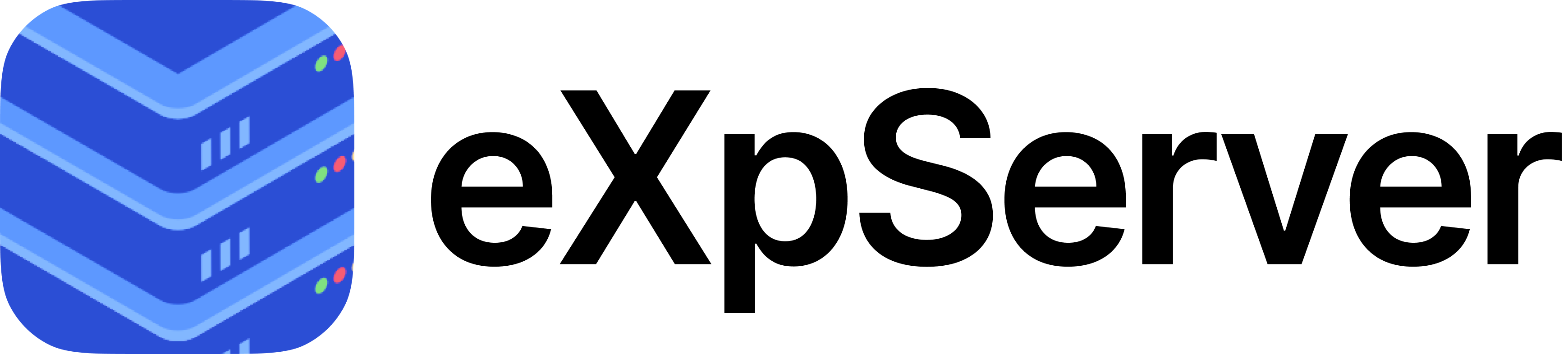

In addition to the data loaded from the executable file, additional segments are allocated among which the most important one is that for maintaining run time data of the stack and the heap. Unix/Linux systems use the same memory segment for both the stack and the heap, with the stack allocated in the higher memory and the heap allocated in the lower memory of the same segment.

A program loaded into memory for execution is called a “process” and the memory allocated to the process is called the “address space” of the process in OS jargon.

Process

A computer program is a set of instructions stored in the file. A process is an instance of a computer program in execution. When the program is loaded into memory and starts execution, the process become active. Each process operates in its own isolated memory space, which consists of four main memory segments:

- Text Segment: Contains the executable code.

- Data Segment: Stores global and static variables.

- Heap: Used for dynamic memory allocation during runtime.

- Stack: Stores local variables and function call information.

Among the above, Heap and Stack are allocated in the same segment with the heap growing upwards from the lower memory and the stack growing downwards from the higher memory.

(Caution: In the following figure, the lower memory starting from the smallest address within the segment is shown on bottom and the upper memory region is shown at the top)

The above image denotes the representation of a process in memory. Here, the arrows represent that both the Heap and the Stack can grow during execution of the process. Heap memory expands during dynamic memory allocation (using the malloc() function) and stack grows due to space allocation for automatic variables and allocation of space for run time activation records during function calls.

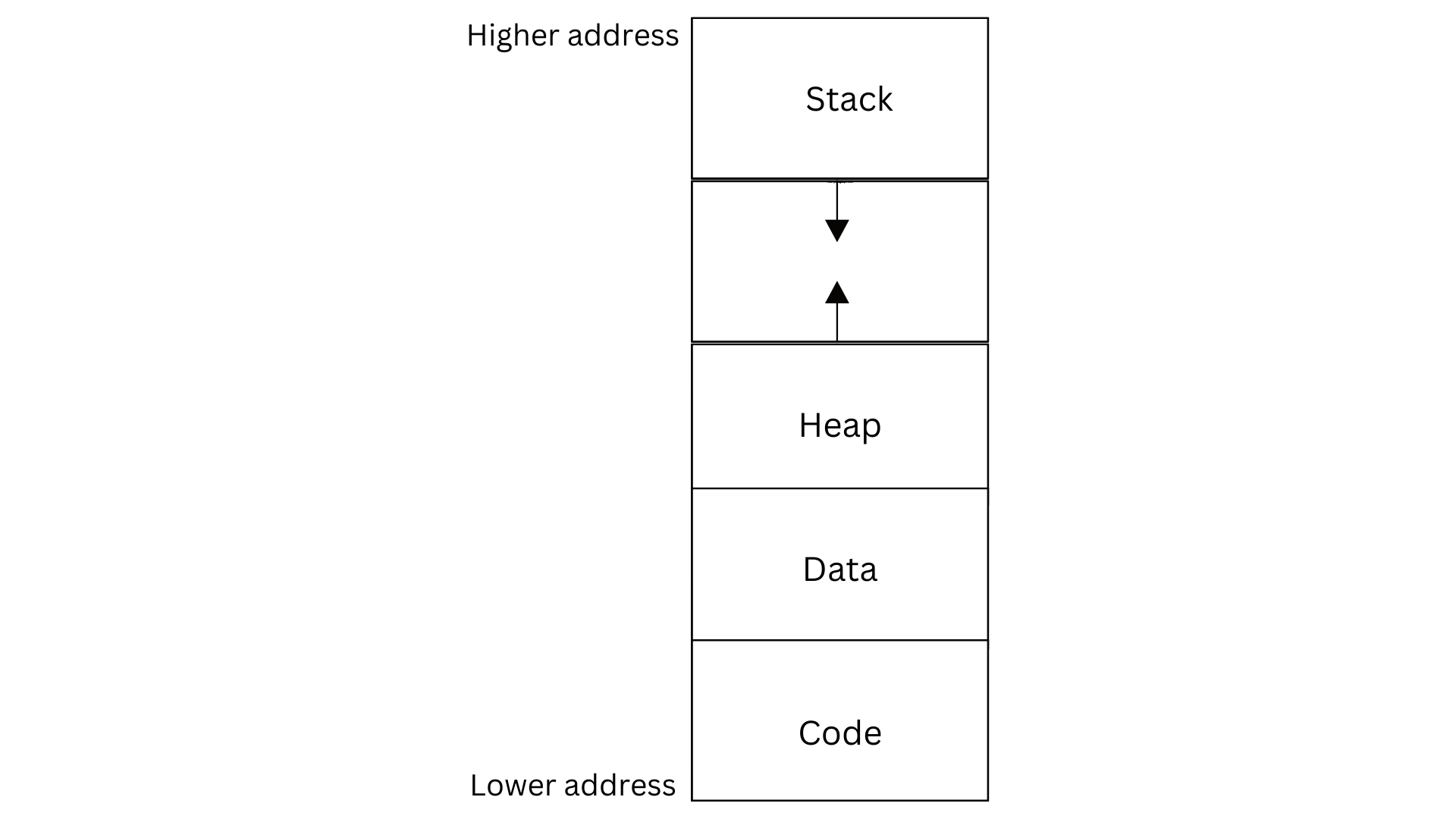

Each process is identified by a unique process id (PID). The OS maintains an internal data structure called the process control block to maintain meta-data pertaining to various processes in execution. Each process has an entry in the PCB. The PID of each process is stored in the PCB entry of the process. The PCB also contains a lot of meta data associated with the process. Let’s look into the structure of PCB in detail.

Process Control Block (PCB)

A process control block (PCB), also called a process descriptor or task control block, is a data structure used by a computer operating system to store all the information about a process. When a process is initialized or installed, the operating system creates a corresponding process control block, which specifies the process state, program counter, stack pointer, status of opened files, scheduling algorithms, etc of the corresponding process. An operating system kernel stores PCBs in a process table. i.e, The Process Table acts as an index which points to individual PCBs. When the operating system needs to perform an operation on a process (e.g., context switching or scheduling), it looks up the process in the Process Table and retrieves the necessary information from the corresponding PCB.

The structure and contents of PCB is given below

- Process ID (PID): A unique identifier for the process.

- Process State: The current state of the process (e.g., ready, running, waiting, terminated).

- Process Priority : Priority level of the process, used by the scheduler to decide which process to execute next and distribute the CPU resources accordingly.

- Accounting Information: Keeps track of the process's resource utilization data, such as CPU time, memory usage, and I/O activities. This data aids in performance evaluation and resource allocation choices.

- Program Counter (PC): Indicates the next instruction to be executed for the process.

- CPU Registers: Stores the values of CPU registers such as stack pointers, general-purpose registers, and program status flags when the process is not executing (to resume the process correctly).

- PCB Pointer: This contains the address of the next process control block, which is in the ready state. It helps in maintaining an easy control flow between the parent and child processes.

- List of open files: Contains information about those files that are used by that process. This helps the operating system close all the opened files at the termination state of the process.

- I/O Status Information: Information on I/O devices allocated to the process, such as open file descriptors, I/O buffers, and pending I/O requests.

- Memory Management Information: Information about the memory allocated to the process (e.g., page tables, base and limit registers).

When the process terminates the PCB entry associated with it is typically removed by the operating system. Which includes the de-allocation of resources(such as memory, file descriptors, and I/O devices) that were assigned to the process and deletion of the PCB block which contains all the execution details of the process from the process table. This allows the OS to free up the memory and resources occupied by the PCB.

Process Creation

exec() and fork()

Processes are created through different system calls. The two most popular ones in Unix/Linux systems are exec() and fork() .

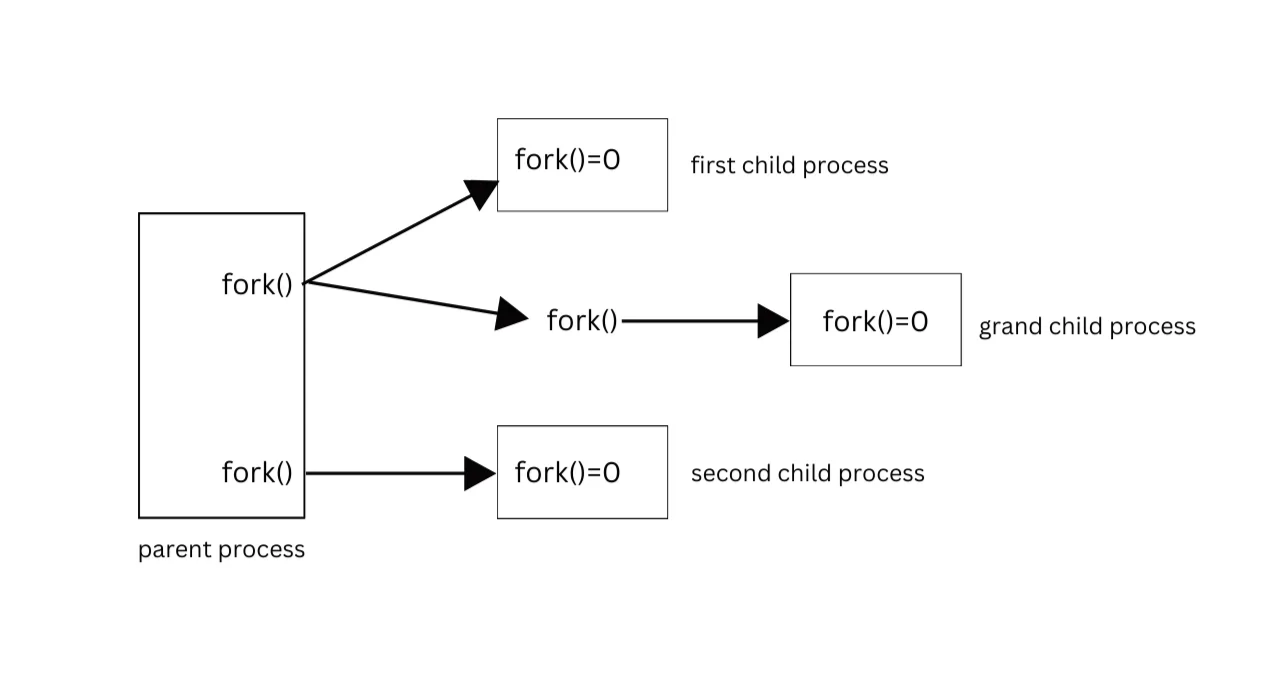

fork(): When thefork()system call is invoked, the OS creates a new memory region (address space) for the child process and copies the contents of the text, data and stack/heap segments of the parent into corresponding segments of the new address space. Thus, the contents of memory allocated to the child process will be (well - almost!) identical to that of the parent at the time of completion of thefork()operation. A separate PCB entry will be created for the child process, and the PCB entries corresponding to files (and other resources like semaphores, pipes or shared memory) opened by the parent will be copied to the PCB entry of the child as well. Hence the child process will also be able to access these resources. Both process continues execution from the instruction immediately following thefork()invocation. Details of the programming interface offork()in Unix/Linux systems is described in fork() system call documentation

exec(): Theexec()system call takes the name of an executable program on the disk as input and loads the program’s text into the text segment of the process that invokedexec(). The contents of stack/heap and data segments of the current process are replaced with the initial configuration of stack/heap and data segments of the newly loaded program. Thus,exec()completely destroys the calling process and replaces it with a new process executing a completely different code. However, the same PCB entry of the calling process will be used by the new program, and as a result, the new program executes with the same PID as the calling process. Hence technicallyexec()does not create a new process, but only “overlays” the current process with new code and execution context. (Linux/Unix systems provide a family of similar functions implementing essentially the sameexec()functionality, but with minor technical differences). Further details may be found in the page [exec]

In the eXpServer project, we want to create server programs that connects to several clients concurrently. One way to handle this is for the server to create (an identical) child process using the fork() system call to handle each client request. However, this is very inefficient because creating a new address space and PCB entry, and then copying all the text, data, stack and heap to the new address space for each client connection would slow down the server considerably. Observe that the code for each child process is nearly identical and these concurrent processes can actually share most of the text and data regions as well as files and other resources.

What is needed here is to create a version of fork() where the child process shares the PCB entry as well as the address space.

Introduction to Threads

Such a simplified version of fork() is provided by threads. Linux/Unix systems allow a process to concurrently execute routines within its code segment as separate threads. To support this kind of “light weight” forking of processes, the notion of “threads” where introduced in Unix/Linux system in 1996 and since then most servers implement concurrent code using threads. A collection of system calls are also provided in Linux/Unix systems to support creation, destruction and synchronization between threads.

INFO

A discussion of the system calls that handle threads is given in the system calls page.

While the heap memory is shared by all threads created by a process, each thread needs a separate stack to be allocated within the same stack/heap segment. The bare minimum “separate data” to be maintained individually for each thread includes the thread’s execution context (values of registers, stack pointer, instruction pointer), local variables, function call stack etc. Each thread is allocated a separate stack within the same stack/heap segment.

Note that while the address space and resources such as files used by a process will be protected by the operating system from illegal access by other processes which do not have the necessary access permissions, threads within a process share the same address space and open files and OS do not provide any protection between threads within the same process. Thus, the efficiency provided by threads shall be used only when a “trusted code” is running concurrently. For our project, we spawn threads to handle client connections to a server, and in this case the threads contain (our own) trusted code, and hence needs no protection from each other.

INFO

Read more from the wikipedia link on threads.

A few years later, it was realized that an even more efficient way to handle concurrent connection requirements in a single server was to avoid creating new processes or threads, but making a single process capable of handling I/O events happening concurrently. The advantage of this approach was that there is no need to maintain separate stack/heap segments or execution contexts for each concurrent connection. Linux epoll is a mechanism introduced in 2001 to support creation of such server programs and they will be used in this project extensively.

The Apache server (1995) uses threads for handling concurrent client connections whereas Nginx (2004) uses epoll.

For a discussion on epoll, see the epoll documentation.

In the current page, we will describe threads.

Threads

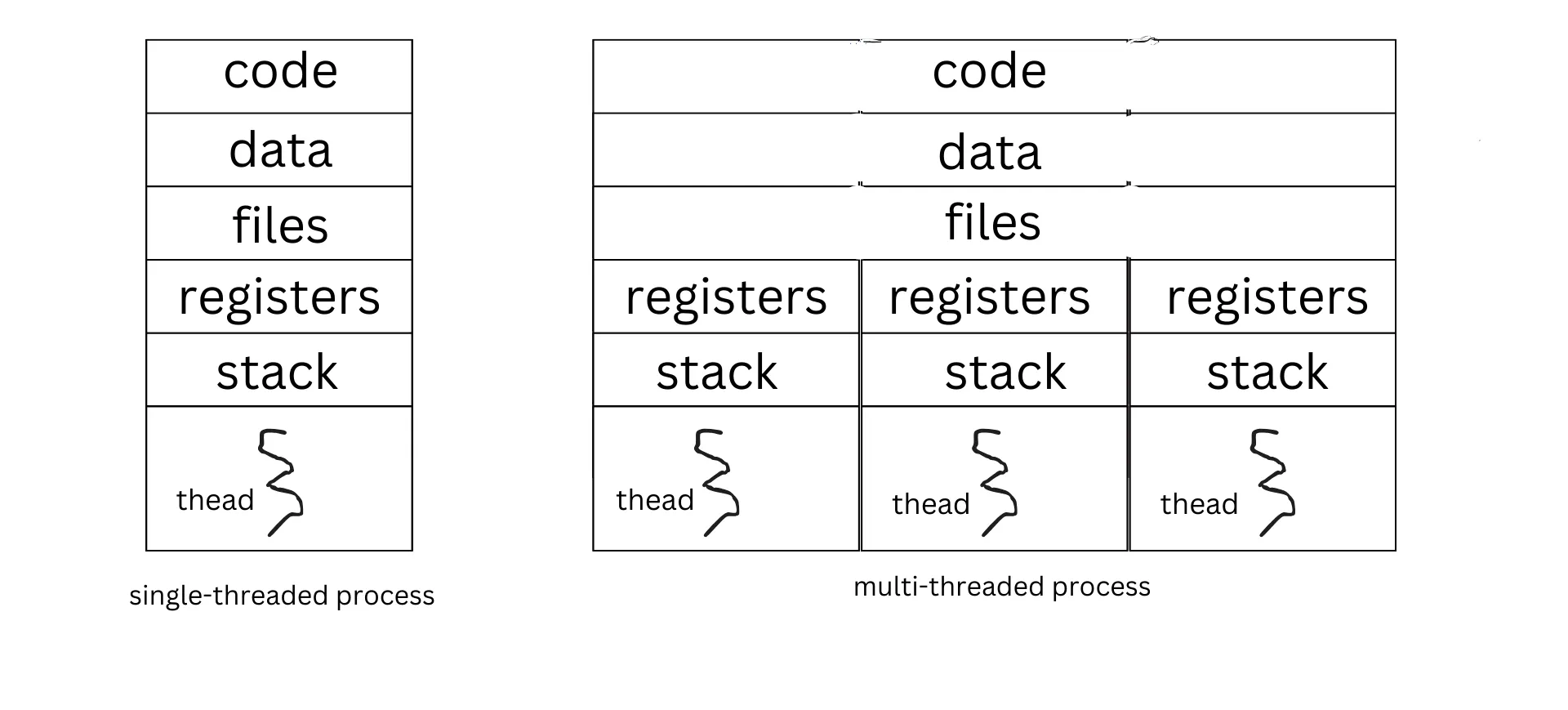

As noted previously, each thread within a process shares a common text, data and stack/heap segments with other threads of the same process, but has separate copies of:

- Stack: It holds the thread's local variables, activation records of function calls, and return addresses and dynamic memory. The stack of all threads of a process are maintained within the same stack/heap segment of the underlying process.

- Register Set: The register set contains the thread's execution context, including the values of CPU registers. These registers include the program counter of each thread, stack pointer of each thread. Since the execution context of each thread within a process needs to be maintained separately, a separate OS data structure called thread control block (TCB) is maintained for each process to keep meta-data on each thread created by the process. The volume of data to be maintained in the TCB entry of a thread will be much smaller than that of the PCB entry of the process, as data on shared resources such as file pointers are stored in the PCB entry only.

- Thread-Specific Data: Thread-specific data allows each thread to maintain its unique state. It can include variables specific to the thread, such as thread ID, state (running/ready/blocked) etc. Such data is also stored in the TCB entry of the thread.

Multi-threading is the ability of a CPU to allow multiple threads of execution to run concurrently. Multi-threading is different from multiprocessing as multi-threading aims to increase the utilization of a single core. Modern system architectures support both multi-threading and multiprocessing.

The main Improvements achieved through multi-threading are listed below

Fast Concurrent Execution : OS schedules multiple threads in the same process concurrently. Since Switching between threads within a process is much faster than context switch between multiple processes, concurrent servers using threads for handling multiple connections will run faster response to each client than servers that spawn a separate process for each client.

Non-blocking Operations: One thread can handle blocking input/output operations while other threads can continue executing without blocking. This allows a process to make effective utilization of the CPU.

The major thread operations which we use in this project are thread creation and termination using pthread_create() , pthread_exit() , pthread_join() and pthread_detach() . Refer the system calls page for more details.

Thread Control Block

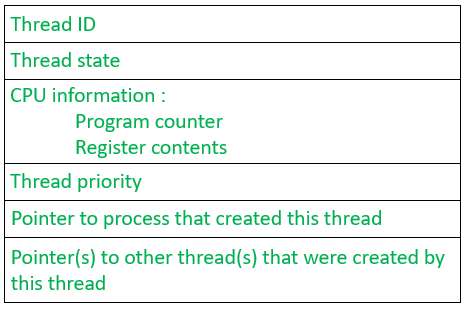

Thread Control Block (TCB) is a data structure in an operating system kernel that contains thread-specific information needed to manage the thread. Unix/Linux systems maintain separate TCB for each process to maintain information about threads created by the particular process. Each thread has a TCB entry which consists of:

- Thread ID: A unique identifier for the thread.

- Thread State: The current state of the thread (e.g., running, ready, blocked, waiting, terminated).

- Program Counter: The address of the next instruction that the thread will execute when it is scheduled to run.

- Registers: The values of CPU registers when the thread is not running. These need to be stored when a thread is preempted or switched out by the scheduler.

- Stack Pointer: A pointer to the thread’s stack in memory. Each thread has its own stack to store local variables, return addresses, and function call data.

- Priority: It indicates the weight (or priority) of the thread over other threads which helps the thread scheduler to determine which thread should be selected next from the READY queue.

- Pointer to the Process Control Block (PCB): Since multiple threads may belong to the same process, the TCB often contains a reference to the PCB of the process the thread belongs to. Threads access meta data relating to process-wide resources like memory and file descriptors from the corresponding PCB entry.

- A pointer to the TCB entries of all threads spawned by the current thread. (This is to enable the thread to access data pertaining to these threads).

- Thread-Specific Data: Any other meta-data specific to the thread which the process maintains.

Once a detached thread terminates, the TCB and all other resources related to the thread (such as its stack and registers) are immediately de-allocated by the operating system.

For programming inteface to threads in Unix/Linux enviornments, see the system calls page.